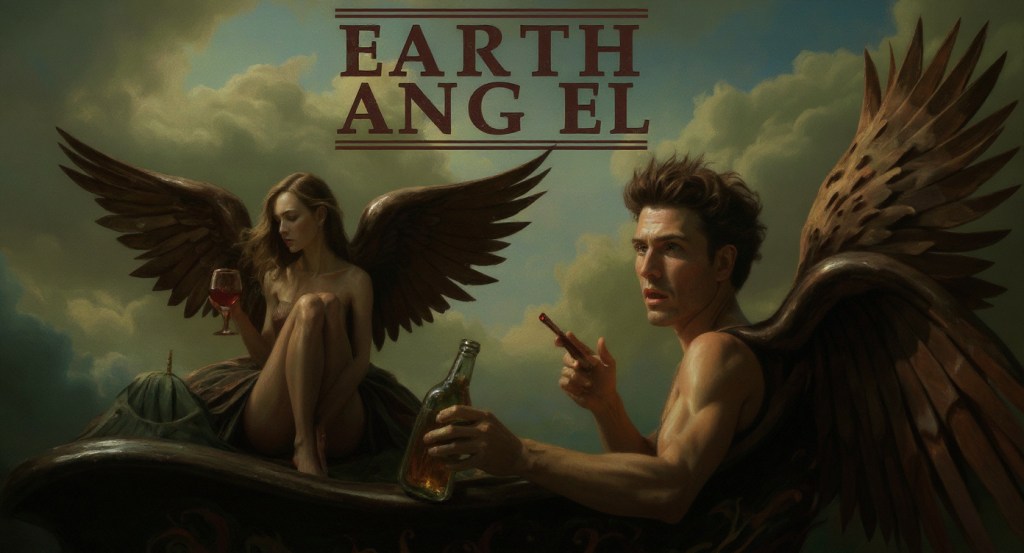

ABOUT EARTH ANGEL

In a quiet village in England at the turn of the 20th century, an angel drops in—literally— changing the resident vicar’s life forever and disrupting the mores of the town.

This play is a creative adaptation of H.G. Well’s “The Wonderful Visit.”

CHARACTERS

ANGEL angel, age unknown.

HILYER vicar, forty-three.

HINIJER Hilyer’s maid, forty-nine.

CRUMP Hilyer’s doctor, fifty-two.

MENDHAM Hilyer’s curate, thirty-five.

AGNES Mendham’s wife, thirty-three.

GOTCH Local landowner, sixty-four.

BARING Bank clerk, forty-eight.

RICHARD Local pianist, thirty-seven.

JESSICA Richard’s wife, forty-four.

HETTY Richard and Jessica’s daughter, eighteen.

Note: to cut down on actors, the actor who plays HINIJER may also play HETTY. The actor who plays MENDHAM may also play GOTCH and RICHARD. Thus eight actors could be employed instead of eleven.

SETTING

The story takes place in Hilyer’s Living Room, Mr Mendham’s Living Room, Hilyer’s Garden, Crump’s Living Room, a Wood, and a Cemetery.

Scene 1

LIVING ROOM

1895, England. HILYER, a vicar, has seen a curate, MENDHAM, into his house.

MENDHAM My wife came home in a terrible state. She is still recovering from the sight of seeing you – yes, you, of all people – with that –

HILYER Yes, I’m dreadfully sorry. But when I explain –

MENDHAM And apologise, I hope.

HILYER No, not that way. This way, the study.

MENDHAM Now what was that woman?

HILYER What woman?

MENDHAM Pah!

HILYER But really!

MENDHAM That creature in light attire – disgustingly light attire, to speak freely – in fact, non-existent garb – with whom you were promenading the garden?

HILYER My dear Mr Mendham, that was an angel.

MENDAM An angel! Vicar, to find a man in your position, shamelessly, openly …

HILYER Bother! Look here, Mendham, you really misunderstand. I can assure you …

MENDHAM Very well, explain.

HILYER Do you believe in angels, Mendham, real angels?

MENDHAM I am not here to discuss theology. I am the husband of an insulted woman.

HILYER But I tell you, ‘angel’ is not a figure of speech, since there is one in the next room!

[MENDHAM looks uncertainly towards the dining room.]

MENDHAM You brought him here?

HILYER So you knew that the angel was a he! You were only pretending to mistake him for a woman.

MENDHAM I am not here to discuss the sex of angels. But I repeat: you brought him here?

HILYER I only know that – inconvenient as it undoubtedly will be – I have an angel now in the drawing room, wearing my new suit and finishing his tea. I can’t turn him out simply because your wife …

MENDHAM [With a hint of threat] Yes?

HILYER Mendham, I may be a weakling but I am still a gentleman.

MENDHAM And your angel? You still owe an explanation to my wife.

HILYER I fired at him taking him for a flamingo, and hit him in the wing.

MENDHAM I thought this was a case for the Bishop. I find it is a case for the Lunacy Commissioners instead.

HILYER Come and see him, Mendham.

MENDHAM There are no angels, Vicar.

[MENDHAM starts to lave.]

HILYER We teach the people differently.

MENDHAM Not as material bodies.

HILYER Come, see him. He is indeed an angel.

MENDHAM No, I don’t want to see your hallucinations.

HILYER Your wife did.

MENDHAM [Insulted] Now look here, Vicar!

HILYER My apologies, Mendham.

MENHAM That is what I was after.

HILYER What you were after?

MENDHAM Your apologies. My wife awaits hers.

[Mendham leaves as HILYER’S maid, Mrs. HINIJER, sees in a Dr. CRUMP.]

HINIJER Dr Crump.

HILYER My dear Dr. Crump, you too! I’m popular this morning.

[HINIJER exits.]

CRUMP Infamous. Hilyer, tell me about this – ahem – gentleman or – ah – angel.

HILYER News does travel rather quickly here – villages should do away with their domestic post.

CRUMP Tell me the circumstances of your meeting with this, um – what do we call him? – Mr. Angel.

HILYER I went out with my gun, you see –

CRUMP To satisfy your ornithological side?

HILYER Yes. I went out with my gun, you see –

CRUMP After lunch?

HILYER Immediately after.

CRUMP You should not do such things, but go on.

HILYER I caught a glimpse of the angel from the copper gate.

CRUMP In the full glare? It was seventy-nine in the shade.

HILYER You don’t …?

CRUMP Forgive me, Hilyer, but you go out on a hot lunch and on a hot afternoon. Probably over eighty. Your mind, what there is of it, is whirling with avian expectations. I say, ‘what there is of it’, because most of your nervous energy is down there, digesting your dinner. A man who has been lying in the bracken stands up and you blaze away. Over he goes. He stands up again in a second, the sun behind him. He tells you he is not hurt because he is an angel. The shock of almost killing a man instead of a bird, well …

HILYER How did you know he was in the bracken?

CRUMP [Discomposed] What? How did I – ? Well … ah … inference. You said you were by the copper gate.

HILYER Dr. Crump, I think it is the angel you should be interviewing. You will remember me saying I shot him in the wing. As a doctor, it is your duty to attend to it.

CRUMP And he still has this wing?

HILYER Well … er … no, it was shattered.

CRUMP Ha!

HLYER He then shed both wings the way certain insects do. I’m certain they’ll grow back.

CRUMP Convenient.

HILYER You don’t believe me?

CRUMP I believe you mistook a natural phenomenon for a supernatural one. Not so unlikely in a man of the cloth. Everything that is, is natural. There is nothing unnatural in the world. If I thought there was I should give up practice and go into your profession.

HILYER You should examine him for yourself.

CRUMP No need; Mrs. Mendham gave quite a thorough description of the specimen.

HILYER Mrs Mendham! Mr Mendham was just here insisting I apologise to her.

CRUMP Amazing powers of observation that woman has. I believe Mr. Angel has a certain effeminate delicacy of the face?

HILYER Now really.

CRUMP And tendency to quite unmeaning laughter. I detest laughter. Especially in self-proclaimed angels. Many of this type of degenerate show this same disposition to assume some vast mysterious credentials.

HILYER I really do not at all accept …

CRUMP Someone will claim him in a day or so. Or perhaps not. It’s a sad thing in a family when it cannot be … suppressed.

HILYER When what cannot be? I don’t think I understand you.

CRUMP Until you picked up this angel, I shouldn’t have believed you could. Hilyer, my dear friend, already tongues are wagging. Listen. This is my diagnosis. Hot afternoon, brilliant sunshine boiling down on your head – it might almost happen to … any of us… But I really must be going. It’s a quarter to five. See your angel (ha, ha!) off before nightfall. Otherwise you really will be implicated.

HILYER Implicated? Dr Crump, I must insist you meet the angel in question.

CRUMP [Abruptly] No! [Less passionately] No, I will not. Hilyer, believe me, I understand. But we must both understand that no one else should. Good day.

[He leaves. ANGEL enters, an attractive and insouciant youth.]

HILYER You heard all that?

ANGEL Are all men as odd as those?

HILYER Why will no one see you?

ANGEL Because that would make me real.

HILYER You see, I’m in such a difficult position.

ANGEL I’m beginning to see. And all because of the way that first man’s – what did he call her? – wife, and the other creatures with her, saw me?

HILYER You mustn’t call them creatures! Those, ahem, were ladies.

ANGEL How grotesque! And such quaint shapes. Burst balloons.

HILYER They were alarmed. You can’t, ahem, get about like so. We have rather inartistic views on clothing down here on earth. Beautiful and natural as I found you, you would be somewhat isolated in society if you persisted in remaining unadorned.

[HINIJER wheels in dinner and a pot of tea.]

HINIJER I got those clothes for you, Vicar. Those clothes you want for … [nodding disapprovingly at ANGEL]’im.

ANGEL For me? [Feeling his shirt] Like these? Delightful! What a mad, quaint world this is. Where are they?

HILYER I’ll have Miss Hinijer bring them to your room.

[HINIJER leaves after baulking slightly at this.]

And yet I can’t help thinking it will be a shame. You look less … radiant in my clothes.

ANGEL Never mind. I’m playing at human. Oh, what are those balloon things, rattling bells outside your window? Hideous.

HILYER Cows.

ANGEL Cows? We don’t have cows.

HILYER No cows where you come from? Up there? What about horses?

ANGEL They’re mythical, silly. We have unicorns, yes. Plenty of those. But these cows – why would anyone even invent them?

HILYER They’re God’s creation. And they’re rather useful. That’s where we get our milk from, which you’ve just poured into your tea – tea, which you like so much.

ANGEL Really? From the cow?

HILYER Yes, from the cow.

ANGEL And what’s this we’re eating?

HILYER Beef.

ANGEL From cow, too?

HILYER Not precisely.

ANGEL Then where?

HILYER I’m afraid it is the cow.

[ANGEL stops eating in alarm.]

You … you don’t eat dead animals up there?

ANGEL Dead?

HILYER [Astounded] Don’t tell me you don’t know death either?

ANGEL [Ominously] I think I do now.

HILYER Yes … yes, you are going to be difficult both to explain, and to explain things to. This world must appear terrible in some respects. And as you come from heaven –

ANGEL – this must be hell.

Scene 2

MR MENDHAM’S LIVING ROOM

MENDHAM and his wife, AGNES, are at dinner.

MENDHAM So that is what he told me: he is entertaining an angel.

AGNES I never heard a more fantastic story in all my life! The only charitable explanation is that Hilyer is mad.

MENDHAM And the uncharitable explanation?

AGNES That this is what comes of having an unmarried vicar.

MENDHAM Agnes!

AGNES Well, you’re married. That makes you much more sound, I should have thought. You will write to the bishop, of course.

MENDHAM No, I shan’t write to the bishop. I think it would be a little disloyal …

AGNES And he took no notice of the last, you know.

MENDHAM I could …

AGNES Yes?

MENDHAM I could write to Austin. In confidence. He will surely tell the bishop. Although you must remember, my dear –

AGNES That Hilyer can dismiss you, you were going to say? My dear, the man’s much too weak! I should have a word to say about that. And besides, you do all his work for him. Practically, we manage the parish from end to end. I do not know what would become of the poor if it were not for me. They’d have free quarters in the Vicarage tomorrow. You will write? It’s shameless!

MENDHAM I will.

AGNES Good.

MENDHAM [After a pause] I suppose he does shames the Apostles with his levity.

AGNES Them also.

Scene 3

LIVING ROOM

The VICAR and the ANGEL are going down to breakfast. ANGEL notices a stuffed bird as he descends the staircase and stops. HILYER turns round.

ANGEL I suppose when you went out with your gun, I was to end up like one of your stuffed birds?

HILYER You have a queer way of making me rethink my habits. Before shooting you in the wing, taxidermy always appeared to me an edifying hobby. However, I am now quite convinced that, if it were not for collectors, England would be full of rarities.

[They reach the bottom of the first flight of stairs. HILYER is about to descend the second, when he notices that ANGEL has become preoccupied with something he can see through the window.]

ANGEL Is that yonder a man?

HILYER That’s a ploughman.

ANGEL Why does he go to and fro like that? Does it amuse him?

HILYER He’s ploughing. That’s his work.

ANGEL Work? It seems a monotonous thing to do.

HILYER It is. But he has to do it to get a living, you know. To get food to eat and all that kind of thing.

ANGEL How curious! Do all men have to do that? Do you?

HILYER Oh, no, he does it for me; does my share.

ANGEL Why?

HILYER Oh, in return for things I do for him. We go in for division of labour in this world. Exchange is no robbery.

ANGEL I see.

[HILYER begins to descend the next flight of stairs.]

What do you do for him?

[HILYER stops mid-step.]

HILYER That seems an easy question for you, but – really! – it’s difficult. Our social arrangements are rather complicated. It’s impossible to explain these things all at once, before breakfast. Don’t you feel hungry?

ANGEL [Meaningfully] Not for beef. [Pause.] Somehow I can’t help thinking that ploughing must be far from enjoyable, for man and horse. And we always imagine horses, where I come from, to be the most noble creatures.

HILYER Possibly, very possibly. But breakfast is ready. Won’t you come down?

[ANGEL remains staring through the window.]

Our society is a complicated organisation. [Pause.] And it is so arranged that some do one thing and some another.

[HILYER starts to descend the last flight of stairs. ANGEL reluctantly follows.]

ANGEL And that lean, bent old man trudges after that heavy blade of iron pulled by a couple of weary, broken horses while we go down to eat?

HILYER A touch melodramatic but yes. You will find it perfectly just.

[HILYER enters the LIVING ROOM where breakfast is laid out, ready. CRUMP is waiting on a couch facing front of stage. Neither HILYER nor ANGEL notice him.]

Ah, mushrooms and poached eggs! It’s the Social System. Pray be seated. Possibly it strikes you as unfair? [Pause.] I daresay you do. When I was a young man I was puzzled in the same way. But afterwards comes a Broader View of Things. Other considerations. (Those black objects are the mushrooms I mentioned earlier). All men are brothers, of course, but some men are younger brothers, so to speak.

ANGEL And women?

HILYER I beg your pardon?

ANGEL Where do they fit in?

HILYER They are not brothers; they’re sisters, whom we are compelled to watch over. But to return to the example of our brothers, there is some work that requires culture and refinement, and work in which culture and refinement would be an impediment. And the rights of property must not be forgotten.

ANGEL How does property have rights?

HILYER I mean the rights of the people who own the property. One must render unto Caesar …

ANGEL Caesar?

[Something offstage catches ANGEL’S eyes.]

Who’s that?

HILYER He was a Roman –

ANGEL No, there.

HILYER There …? You mustn’t point. It is considered rude in our society. The person to whom you refer is Delia.

ANGEL She, too, always appears to work.

HILYER You know, instead of explaining this matter to you now (drink your coffee; it’s like tea but stronger – it keeps you alert for life) I think I’ll lend you a few books on the theme which sets out the whole thing very clearly. [Noticing that ANGEL hasn’t touched his plate] Not hungry? Mrs Hinijer isn’t used to cooking without meat. Yes, on the surface, it can appear unjust. (Hmm, these mushrooms are well up to their appearance). But of course when viewed –

ANGEL Is she a lady, too?

HILYER Lady? Who?

ANGEL Delia?

HILYER Delia! Oh, no, she is not a lady. She is a servant.

ANGEL Yet those women I startled yesterday – in my ‘state of undress’ – they were ladies?

HILYER Yes, ladies.

ANGEL [Gesturing in DELIA’S direction] That one had rather a nicer shape.

[CRUMP stands up from the couch abruptly.]

CRUMP Indeed!

HILYER Dr. Crump!

CRUMP Marvellous good acting, Mr. Angel. Very saucy. I used to tread the boards myself. Forgive my surprising you, Hilyer. Mrs Hinijer said you weren’t long coming down to breakfast and I could wait in here. I was most keen to hear how this young man might present himself when not under the watchful eye of an expert.

HILYER Dr. Crump, you are always welcome here, but two visits in as many days – the gossips will view this house as one of illness.

CRUMP A diagnosis not unfounded.

HILYER I beg your –

CRUMP [Cutting HILYER off; to the Angel] Journey tire you yesterday, young man?

ANGEL I am still quite stiff.

CRUMP [Embarrassed] I daresay you are. How nice of you to partake of the quaint custom of clothes today. Still, what with the weather and your exertions in the bracken, I expect you must’ve been quite hot. You did fly all the way down from the fiery Empyrean, ’ey? No conveyance?

ANGEL I was flying up a symphony with some Griffins and –

CRUMP Flying up a symphony, were you? Suppose yourself some sort of Mozart, do you?

HILYER Our friend is the most exquisite violinist, Dr Crump. I have not heard more beautiful music.

CRUMP A fool with a fiddle, ’ey? Is that what you are?

ANGEL Yes, I was flying up a symphony and suddenly everything went dark and I was in this world of yours.

CRUMP Likely story. [Pause; another tact] I suppose you know this world of ours quite well, viewing it as you do from your elevated position. And you’ve singled out your target, too, a person most credulous? ’Ey?

HILYER My dear Doctor Crump, you malign the character of our friend, and mine also. His appearance in our world, he assures me, was quite accidental, if not unwanted.

CRUMP He assures you? [To ANGEL] Yet you’ve seen this world many times, have you not, Mr Angel?

ANGEL Not very well. We do glimpse it sometimes.

CRUMP Oh yes?

ANGEL In nightmares.

[Pause.]

It’s not simply the wings make the angel.

[CRUMP laughs suddenly.]

CRUMP You’re a ‘dorg’, sir, a ‘dorg’ of the highest degree! I must congratulate you. I don’t know how long you will last, but you are keeping it up remarkably well. You make slips of course, but very few. And how long can we expect this charade? You can’t impose on Hilyer’s hospitality forever.

HILYER Yes, I suppose we shall have to put you to work.

ANGEL [In horror] Work!?

CRUMP At last he breaks a sweat!

ANGEL [To HILYER] Like that poor ploughman – that sort of work? [Hopefully] Or your work, which appears to me leisure?

HILYER Probably the former, sadly. As you’ve no references… Do you come from a good name?

ANGEL ‘Come’ from?

CRUMP Oh, yes, a ‘dorg’, a ‘dorg’! Don’t be obtuse, man. You were born, weren’t you? Parents? Dadda, Pappa, Daddy, Mammy, Pappy, Father, Dad, Govenor, Old Boy, Mother, dear Mother, Ma, Mumsy… No good?

ANGEL Why must a reference or a family connection determine the sort of work one does? Surely ability plays a part? I want to live as you or Hilyer – not like your servants.

CRUMP Of course you do. Your motive becomes ever clearer to me. A man sometimes forgets who he is and thinks he is someone else. Leaves home, friends, and everything, and pretends to himself he is born to better things, when deep down he is… well, some of us are brothers, so to speak, and some of us…

HILYER [Less convinced of the rhetoric] …younger brothers.

CRUMP Yes, there is some work that requires culture and refinement, and some in –

HILYER – which culture and refinement would be an impediment.

CRUMP [Slightly disconcerted that HILYER is finishing his sentences for him] Yes, thank you, Hilyer.

HILYER How false and shallow that sounds when hearing it from another! Dr. Crump, behold him! He is an angel –

CRUMP Angel? Pah! [To ANGEL] Young man, I think it jolly regrettable to see this poor old fellow hypnotized, as you have certainly hypnotized him. I don’t know where you come from or who you are, but I warn you I am not going to see the old boy made a fool of much longer.

HILYER Dr. Crump, I know your concern proceeds from a good place but –

CRUMP It won’t do, Mr. Angel! I am not one of the dupe class. I think I know a little of this world, whatever I do of yours, young man, but you will go back to it.

HILYER [To CRUMP] What do you mean: whatever you know of his world?

[CRUMP, caught out, opens and closes his mouth without sound. At last he recomposes himself.]

CRUMP Hilyer, if you will allow me a moment in private? [HILYER accompanies CRUMP to the front of stage.] We have been friends for a very long time, have we not? No, it is not necessary that you answer. In a village, one must get along with one’s neighbours. People will have their … idiosyncrasies. Yet it is important they hide them for the stability of the whole. There is one inmate in this village, you will be aware, who has transgressed these tacit boundaries. Baring.

HILYER Baring? Oh, dear, you bring up his name in connection with mine?

CRUMP Only as a foretaste of how others will.

HILYER But why – ?

CRUMP His name was once linked to mine.

HILYER Oh, oh, I don’t want to hear this! I’ve never inquired into your history.

CRUMP No. [Pause. Rethinks how to tackle the subject] Hilyer, I risk myself in warning you of the risk to yourself. Even alluding to what I am about to allude can have the gravest consequences. I hope you will do justice to my confidence.

HILYER You are frightening me, Dr Crump.

CRUMP As it should.

HILYER ‘It’?

CRUMP It is that very thing Baring was considered guilty of. And guilt can rub off if you brush too closely against it.

HILYER I won’t listen – I don’t know what you mean!

CRUMP Hilyer, you know the nature of his infamy.

HILYER I don’t – I don’t!

CRUMP Baring struggles to get work, only managing to find a petty clerking job at the bank. He is ignored in society. You see how he is ostracized.

HILYER Indeed!

CRUMP Your angel must go back.

HILYER Oh really, why?

CRUMP [With severe gravity] I do not believe you, Hilyer, could brave the consequences. Without meaning to be insulting, you haven’t the courage.

[HILYER ponders whether CRUMP is right. ANGEL, who has by now wandered over to HILYER and CRUMP so he can hear their conversation, interjects.]

ANGEL Go back?

HILYER Yes, what ‘world’ would you send him back to?

CRUMP That of the working class!

ANGEL Like that ploughman? And Delia? Be imprisoned? My labour to belong to another man?

CRUMP If you don’t leave Hilyer alone I shall communicate with the police!

ANGEL The police? Prison?

CRUMP I knew you would know what those things meant.

HILYER Because I have explained them to him, dear Crump! I must say, in explaining this world to one new to it, I have felt a deep shame for not having questioned it so long.

CRUMP Hilyer, it’s the questioning that’s shameful. Each in his rightful place. It’s the aspiring that makes people miserable, not their portion. And you, Mr Angel, shall be made to work. Good day to you. Hilyer. [Starts to leave but stops.] I almost forgot the purpose of my visit in all this turmoil. Hilyer, I shall see you at my soiree Saturday noon?

HILYER Your soiree …?

CRUMP You haven’t confirmed.

HILYER Oh yes, of course.

CRUMP [Nodding at ANGEL] And alone.

HILYER Alone?

CRUMP Yes, alone.

[CRUMP leaves. HILYER regards ANGEL.]

ANGEL What is this life of yours about?

HILYER We have found answers in certain beliefs, but those beliefs simply bring up more questions. One may even be a churchman and disbelieve. What a life I’ve led! A silly pink helpless thing, wrapped in white, with goggling eyes that yelped dismally at the Font. Then a boy, full of great hopes and dreams, vague troubling emotions and unexpected dangers. Then life began in earnest. A not very glorious youth. Sickly, too poor to be radiant and … and, yes, with a timid heart. A heart filled with a passion that would have taken a greater courage than mine to act upon. Dr Crump is right; I am not a brave man. What was there for me but to take orders, while the young men and women round me paired off – most of them? And now they come to me shy and bashful, in their smart ugly dresses, and I marry them off. When they return with their silly, pink, helpless babies, they want me to say a name and some other things. And these bashful couples, once youths and maidens, are some fat and vulgar, others thin and shrewish, and they get a queer delusion of superiority over the young people and all the delight and glory goes out of their lives, and so they call the delight and glory of the young ones Illusion. [Pause.] And in the end, I bury them, and read out of my book to those who will presently follow into the unknown land. I stand at the beginning, and at the zenith, and at the setting of their lives. And on every seventh day, I who am a man myself, I who see no further than they do, talk to them of the Life to Come – the life of which we know nothing. [Pause] The battle of the flesh and spirit had stopped troubling me … till now.

ANGEL Yah-oh! Dear me! A higher power seemed suddenly to stretch my mouth open and a great breath of air went rushing down my throat.

HILYER You yawned. Do you never yawn in the angelic country?

ANGEL What does it mean?

HILYER I suppose you want to go to bed.

ANGEL [Suggestively] And what’s that? You must show me.

Scene 4

LIVING ROOM

The VICAR is wringing his hands in turmoil. He approaches the door to ANGEL’S room and knocks on it. There is no reply.

HILYER My dear Angel, I prayed all last night after I left you – I prayed in shame but nothing would come. There was only the one resounding answer to my question. And the answer was mine. Why must I miss out on the jubilation of life?

[The door opens and out walks HINIJER, sheets in hand, much to the surprise and consternation of HILYER.]

HINIJER Jubilation of life? I’ve just cleaned your so-called angel’s room, and a right mess he left it in.

HILYER Oh, dear, ah, um, Mrs Hinijer, so our guest is not in today?

HINIJER Not ’im as you’re referring to. But there’s another waiting downstairs for you. I couldn’t find you so I went back to my chores. Sir John Gotch.

HILYER Sir John Gotch?

[GOTCH enters.]

GOTCH Yes, Sir John Gotch.

HILYER Sir John Gotch! To what do I – ?

GOTCH Vicar, I believe you’re harbouring a criminal.

HILYER [Turning white] A criminal?

GOTCH May I ask who this Mr. Angel is?

HILYER Oh, it is to him you refer?

GOTCH Naturally, unless you’ve others holed up in here.

HILYER Oh, you joke.

GOTCH Not at all, sir, not at all.

HILYER What … ah, what crime do you suspect him of?

GOTCH Crime? Do you know, he’s been going about this village preaching Socialism?

HILYER [Relieved but surprised] Socialism? I’m relieved.

GOTCH Relieved? Socialism – relieved? He’s been buttonholing every yokel he’s come across, and asking them why they had to work while we – I and you, you know – did nothing. He has been saying we ought to educate every man up to your level and mine out of the rates, I suppose, as usual. He has been suggesting that we – I and you, you know – keep these people down. Pith ’em.

HILYER What was that?

GOTCH Pith ’em.

HILYER Pith ’em?

GOTCH Ever heard of a pithed frog?

HILYER No?

GOTCH You go in for taxidermy. Don’t you know?

HILYER No.

GOTCH Must be vivisectionists, in that case. They take a frog and they cut his brains out and they shove a bit of pith in place of them. Somehow your guest got hold of this crude metaphor for describing the working class in our illustrious village. They’re a bunch of pithed frogs, apparently, who run about spry and do all the dirty work, and feel thankful they’re allowed to live and, what’s more, who take a positive pride in hard work for its own sake. According to your guest, in that case they must be pithed. Don’t know where he got that image of pithing – was half afraid it was you, given your queer hobby with birds.

HILYER Dear me, I had no idea.

GOTCH If we don’t come down on him pretty sharply –

HILYER A Socialist?

GOTCH You see why I am inclined to push matters against our gentleman though he is your guest?

HILYER My guest? Really, I had no choice.

GOTCH In that case, it seems to me he has been taking advantage –

HILYER [In horror of being found out] Taking advantage?

GOTCH [Perplexed] Of your hospitality. What else?

HILYER Nothing else. Naturally.

GOTCH Well, then?

HILYER Oh no, to be truthful, it’s not quite like –

GOTCH So there’s one of two things. Either that ‘guest’ of yours leaves the parish or I take proceedings. That’s final.

[Pause.]

HILYER Sir John Gotch, do not take offence, but I will simply not … I mean, what you ask … You see … I won’t.

GOTCH [Furiously] What?

HILYER Arrangements will be made.

GOTCH I’ll give you a week.

HILYER Thank you.

[GOTCH half leaves then turns back.]

GOTCH Look here … I mean, sorry to give you this bother. But the situation is intolerable, of course.

HILYER A week.

GOTCH A week.

[GOTCH leaves. Pause.]

HILYER I even thanked him.

[Pause.]

No, no, he is staying. And I will tell that hideous man to –

[HILYER rushes to the door, perhaps to pursue GOTCH, when HINIJER bars his way.]

Mrs Hinijer!

HINIJER Begging your pardon, sir, but might I make so bold as to speak to you for a moment?

HILYER Well?

HINIJER May I make so bold, sir –

HILYER Please, to the point, Mrs Hinijer.

HINIJER [Yelling] As to arst when Mr Angel is a-going?

HILYER Another!

[HILYER again starts to leave.]

HINIJER I’ve been used to waiting on gentlefolks, sir, and you’d hardly imagine how it feels to wait on such as ’im.

[This stops HILYER. He returns through the door.]

HILYER ‘Such as ’im’? Do I understand you, Mrs Hinijer?

HINIJER We-ell, sir, I don’t know as I understand you – a perfect gentleman. There’s a good deal of talk in the village.

HILYER [Frightened once more] Is there?

HINIJER Before I came to you, sir, I was at Lord Dundoller’s seventeen years, and you, sir – if you … That Mr Angel ain’t what you think he is, sir.

HILYER You mean an angel?

HINIJER [Slowly] What I mean to say, sir: that Mr Angel is a – there’s no polite word for it – but he’s ‘one of them’. And since ’e’s one of them, and you’ve taken ’im in, in no little time people will get to saying you must be one of –

HILYER Enough! Mr Angel will be leaving this house in the course of a week. Is that satisfactory?

HINIJER Quite. And I feel sure, sir –

HILYER Certainty!

Scene 5

LIVING ROOM

HILYER is sitting with ANGEL at breakfast. HILYER cuts open a letter with an envelope knife and reads its contents. When he is finished, he puts it down, devastated.

HILYER I don’t believe it.

ANGEL You creatures make a great fuss of what you do and don’t believe.

HILYER I don’t believe it.

ANGEL You mean, in this instance, that you do believe it but don’t wish to?

HILYER I do believe it.

ANGEL I thought so.

HILYER Dr. Crump has uninvited me to his soiree Saturday noon. Apparently Mrs Mendham is still creating a storm over why I should have been found with you in all your Adam-like freshness and Sir John Gotch …

ANGEL Yes?

HILYER I promised him you would be gone from my house in a week. And, from this letter, it would seem that he has told Dr Crump that he is going to keep me to my word. That leaves us six days.

ANGEL And then you’re kicking me out?

HILYER The brief enjoyment of a momentary pleasure cannot be the cause of ruin of one’s whole life …

ANGEL You’re kicking me out, where I will have to fend for myself? Work?

[Mrs HINIJER enters, flustered.]

HINIJER Sir!

HINYER What is it, Mr Hinijer? Calm yourself.

HINIJER Sir!

HINYER Yes?

HINIJER Could I please speak to you in private, sir?

HILYER I have no secrets from our guest, Mrs Hinijer.

HINIJER Sir, please.

HILYER Very well.

[HILYER walks with HINIJER to front of stage where they speak confidentially.]

HINIJER Perhaps I was wrong about your guest, sir.

HILYER My guest?

HINIJER [Pointing to ANGEL] Yes, ’im. Wrong.

HILYER I am very glad to hear it, Mrs Hinijer. If only certain other residents of this village could also find it in themselves to be more welcoming. I trust you will now treat him as a gentleman?

HILYER Wrong? Not about that! Which way he leans, I meant. If that Mr. Angel was a gentleman (which he isn’t), he’d feel ashamed of hisself. And her (Delia) an orphan too!’

[The doorbell rings.]

HILYER Delia?

HINIJER Excuse me, Sir.

[HINIJER leaves.]

HILYER Delia? [To ANGEL] Have you been in infelicitous communication with my servant girl, Delia?

ANGEL She of the nice shape!

HILYER My dear Angel! There are some divisions in society that, though they may appear arbitrary, are very much ruled with a higher and more lofty purpose. In respect to masters and their servants, one should –

[HINIJER enters again, twice as flustered as before.]

HIINIJER Sir!

HILYER Yes, Mrs Hinijer!

HINIJER Again, in private, sir?

HILYER The loneliness of secrecy!

[Grudgingly, HLYER acquiesces, following HINIJER to the front of stage.]

HINIJER P’raps I was right the first time, sir.

HILYER The first time?

HINIJER Otherwise, why would he be here now?

HILYER Who was at the door, Mrs Hinijer?

HINIJER I can’t think why, sir, but it’s that horrible man – he’s says he’s here to see you, sir. Yes, you!

HILYER To whom do you refer, Mrs. Hinijer?

HINIJER Baring.

HILYER [Surprised; more loudly than he intends] Baring? [Lowering his voice] But why …? Tell him to leave.

HINIJER If you don’t mind the liberty, sir, I already did. He won’t. He said he’ll be in any moment if he has to wait more’n a moment.

[HILYER tries to think what to do. At last he turns to ANGEL.]

ANGEL Another ‘worthy gentleman’ who doesn’t approve of my being here?

HILYER Sarcasm! Only days ago, you never knew such things. I shudder even to wonder why Baring pays me a visit. His society is even more shunned than ours. Please, if you will excuse me I must sort out the matter of this unexpected nuisance. My dear angel, if you would be so kind as to retire to the garden.

ANGEL I prefer the outdoors

[ANGEL leaves.]

HILYER What shall I do, Mrs Hinijer? Baring here? What can he want with me?

HINIJER I don’t know, sir; he only said –

[BARING barges in.]

BARING – that we might at last have found common ground. Good morning, Vicar.

HILYER Sir … Sir, I beg you to leave. You must have the wrong house.

BARING No, I have the right house. In you I have the right person. May we be allowed to be frank with each other? [Referring to MRS HINIJER with a nod] In private?

HILYER Have I a choice?

BARING It depends on the manner in which you wish me to leave.

[HILYER considers his options. At last he turns to HINIJER.]

HILYER Yes, thank you, Mrs. Hinijer.

[MRS HINIJER hesitates to leave.]

HINIJER But, Sir?

HILYER Please leave, Mrs Hinijer. Is not God’s door open to all?

BARING [Bristling] I am not here seeking charity. But as you wish.

[HINIJER leaves.]

Vicar, as you must be aware, in my youth I was involved in a very nasty scandal. I was hounded out of what public life this village has to offer.

HILYER I don’t understand how I may …

BARING It takes a similar shame to make a man feel sympathy.

HILYER You can’t possibly … what shame?

BARING Stories are already circulating around you. Mrs. Mendham in particular …

HILYER Yes, I must make my explanation to her before she completely tars me with false reports. If you’ll excuse me, I was just on the point of paying her a visit and explaining –

BARING [Barring HILYER’S way] Explaining? What can you explain, Vicar, to a person who has already made up his mind?

HILYER Which makes my visit all the more –

BARING Impossible.

[Pause.]

HILYER I am not sure how I may help you. Or you me, for that matter.

BARING Do you think that men who have committed what the world calls a crime should be forgiven?

HILYER Never!

BARING Never? What a Puritan you are, Vicar. How dull to have to be a civil old dowager. I got in trouble in my youth. It never came to court. Nothing was ‘proven’. Just as you are now in trouble. You must know my story.

HILYER I do not.

BARING Ignorance in children is innocent; in adults, criminal. Since you seem intent upon making me recall the circumstances of my iniquity, recall them I shall. Beyond the copper gate, in the very same bracken where you found your guest naked, I was found twenty years ago with a gentleman in circumstances similar to yours. In that instance, the gentleman in question wormed his way back into the town’s good graces; my reputation remained tarred. But we, meaning you and I, Vicar, must both win back respect in this town. The thing that once ruined my reputation if you are not clever is that same that jeopardises yours.

HILYER I have done nothing wrong.

BARING You needn’t have to be found guilty. I am proposing that you expel the youth.

HILYER Expel …?

BARING And any feeling you have for him. Make it be known in town that you were too eager in satisfying your charitable nature by taking him in, and now he has taken you in. You will see this is the easier course, and it was the course taken by the clothed gentleman in my own case. If you cannot, merely witness my life as an example of the harder road. All I ask when the innuendo dies down is this: would you please be so good as to use your influence on my behalf?

HILYER My influence? On whom?

BARING On society, of course! My tireless and quiet work in the bank has gone halfway to repairing my reputation; I now want to go the rest of the distance. Help me regain admittance into society. Until this slight hiccup, your reputation was spotless. When this minor hitch is forgotten, whose word would have better currency than a vicar’s? You will be forgiven. And your forgiveness of my past transgression will lead the way to others welcoming me in. [HILYER is silent.] Will you say nothing? I could have appealed to your compassion in making my plea. Told you of my hardships, my misery, my poverty. I have spared us both that. [HILYER remains silent.] Will you help me? Speak!

HILYER Mr Baring, I cannot be associated with you in any way. Even your being here is proof of only one thing, but a very frightening thing at that: your character and predilections have been associated with mine.

BARING My ‘predilections’? Then you do know my story?

HILYER I only meant –

BARING Your lying to me means you may lie to yourself. I think we both know what that lie might entail.

VICAR I do not understand you.

BARING Very well. If you insist. Then I must make recourse to my second option. I too was strolling in the bracken these three days past. (Let’s say I now and then reminisce).

VICAR Oh, how vulgar!

BARING I saw you and your supposed angel. I can make it known exactly what I did see: congress of an intimate nature.

HILYER How dare you! I was involved in no such thing, not that it were possible between two men.

BARING Then you have tried to imagine the conjunction?

HILYER Why, you –

BARING You what? Vicar, I know you don’t approve of me. A certain supposed crime has been linked to my name, a name that comes down from Sir Giles Baring himself, I might add.

HILYER A good name? You do not have a good name.

BARING And nor will you if you persist in this course. Think of the further scandal, Vicar. It is already alight; with my testimony I could fan it into a conflagration. As you say, linking my name to yours would alone make you guilty by association. I doubt you would survive. You hold a position in society, it is true, but that very position makes you so vulnerable. Think of that and your fortune. Your ample annuity makes your life so agreeable. But it could all be turned to ashes. My life won’t bear examination, but then, can yours?

HILYER So you saw this, did you?

BARING Yes, I saw you sporting with the angel.

HILYER You saw? What did you see, exactly, Mr. Baring? It was … it was sixty-nine in the shade. In the brilliant sunshine, your mind, what there is of it, and I say what there is of it because … because most of it is in the gutter! Your mind mistakes a natural phenomenon – no, I mean, a perfectly innocent phenomenon – for an unnatural one. Again, I ask what did you see?

BARING [Less sure] I saw …

HILYER Yes? In the full glare? Make your report to the community, Mr Baring. We shall see whose version of events is held in higher esteem.

BARING Perhaps … perhaps, Vicar. Perhaps it is my mistake … this time. But I’ll be watching you.

HILYER As I you. Get out.

[HINIJER enters, flustered.]

HINIJER Sir, it’s Dr. Crump! He’s here to see you!

HILYER Oh bother!

BARING [With distaste] Him!

HILYER If he finds you here … you must go out the back. [BARING obstinately remains.] Mrs Hinijer, detain Dr. Crump as long as you can. [HINIJER leaves. HILYER turns to BARING.] I know Mr Tussles, the bank manager. If you do not leave immediately, I shall make sure you lose even your miserable clerking job. As you have endeavoured to demonstrate: one may fall low; but one may fall even lower.

[BARING relents. He hides in the garden.]

Oh, dear. Courage. In me! I’m shaking all over. And I … I threatened. I made a threat. I blackmailed. But he knows. He knows! And considering the viral nature of gossip, that must mean the whole town suspects.

Scene 6

GARDEN

BARING wanders into the garden where he sees ANGEL sitting on a bench looking up into the sky.

BARING [Lasciviously] So you’re an angel, are you? I should say you are!

ANGEL You’re the second person to believe me.

BARING Second to that scurrilous Vicar?

[ANGEL says nothing].

You are most proper in not damning your saviour. You, the Vicar, myself – we three are eccentrics. As a once-dear person to me is fond of reciting, ‘Eccentricity is immorality. And if a species is rare, it follows that it is not fitted to survive. But we are concerned with the facts of the case, and have neither the desire nor the confidence to explain them. Explanations are the fallacy of a scientific age.’ And, in my own words, there is no explaining us.

ANGEL Us? You talk as if we had something in common.

BARING Have we not?

ANGEL You speak in riddles.

BARING We must, though, mustn’t we? To be safe.

ANGEL Must we?

BARING I’m being bold? Boldness has got me in trouble in the past. But then I had something to lose. Now I have everything to gain. I have instincts, Mr. Angel, like a fox. And a fox needs its instincts to survive. Also … to mate. But it is a solitary creature. A fox can sniff out its own kind … And yet the unfairness of it! Why should a fox be ashamed of hunting lambs, but not the hound of hunting foxes?

ANGEL What is your particular shame?

BARING My … my particular shame? Well … well, you are a plucky fellow, first making yourself at home here, and now … But I warn you, the ruling class allows certain transgressions, but only among its own. However, my shame, as you put it, was in being found, like you, naked with a clothed and supposedly ‘worthy gentleman’.

ANGEL Ah, ‘worthy gentleman’. And this was a – what did the Vicar call it? – a sin?

BARING A great sin.

ANGEL And yet nothing was ever ‘proven’?

BARING Nothing need be proven. The mud can still stick.

ANGEL What did you and this ‘worthy gentleman’ do?

BARING We sported.

ANGEL As the fox and the lamb?

BARING You catch on quickly.

ANGEL And how did you make your kill?

[BARING whispers in ANGEL’ S ear.]

ANGEL [Yawning] Is that all? That is how we angels pass the time.

BARING And how you and Hilyer have passed the time?

ANGEL We have, but it is only after much dilly-dallying or him getting drunk, and then he goes through such a time of self-censure afterwards that it is becoming tedious.

BARING Thank you for the information.

ANGEL Is information so important?

BARING It is the currency of the new age.

ANGEL And what happened to this ‘worthy gentleman’ in your case?

BARING This particular ‘worthy gentleman’, only a few years my senior, has gone on to become a respected doctor in this village.

ANGEL Dr Crump. Why did the mud not stick to him?

BARING There are two orders of punishment in the world, that meted to the poor, and that brushed over the rich. [Bitterly] With your testimony, I have evidence against the Vicar. But the evidence of the poor is nothing to the information provided by the rich. And his word is the richer mint. It is almost funny. Just now, I tried to blackmail the Vicar and he ended up blackmailing me!

ANGEL What is blackmailing?

BARING It is when you have something over someone that they don’t wish other people to know. Therein lies your leverage.

ANGEL [Boastfully, secretively] I have something that a great many people don’t want a great many other people to know.

BARING [Dismissively] Yes, I have overheard of your going round the village trying to change the world.

[ANGEL is disappointed BARING knew straightaway what he meant.]

Socialism?

ANGEL Yes.

BARING That the rich keep down the poor. Pith ’em.

ANGEL Everyone knows this?

BARING The poor know it in their bones, the rich in their pockets. Work is as dirty a word to you, evidently, as it is to me. But let me give you some advice: it is much easier to adapt to the world as it stands than wrest it into shape.

ANGEL How do you mean?

BARING What I propose to you is that you stop trying to change the world to how it should be, and convince the world that you comply to its norms. How you were found was how I was found. In the very spot Hilyer discovered you.

ANGEL And that is what prevents you from good society, the leisured society? You must have someone of good reputation discount the charge? I am under the same charge?

BARING For a foreigner, you understand the situation perfectly.

[HILYER enters.]

HILYER Baring, you must go out the back way.

BARING But my scheme for your helping me return to society, means I should be seen to exit through the front.

HILYER And ruin my name further? I have Dr. Crump delayed in the front room.

BARING A prickly situation for you. Vicar, I will agree to leave by the back if you agree to listen to my terms.

HILYER I will not.

BARING You refuse, when I have already heard a confession from your companion here, on the ‘sins’ you two have committed?

HILYER My dear angel, you haven’t …?

ANGEL [To BARING] This is the blackmail you spoke of?

BARING Yes, you see how it is like a shifting hand in cards. Now we hold the ace.

HILYER Angel, you are in on this too? Let me tell you, I won’t be blackmailed by a homeless, lying tramp!

BARING At last, my dear Vicar, you are beginning to conform to the course I am counselling you to take. Now will you listen to my terms?

HILYER If I must, I must.

[BARING looks at ANGEL.]

Mr Angel, if you could wait in the house.

[ANGEL looks long at HILYER before walking inside. HILYER won’t return the gaze.]

Scene 7

LIVING ROOM

ANGEL enters the living room and sits down, wondering what to do. CRUMP barges in.

CRUMP Hilyer, I won’t be kept waiting any – ! Oh, it’s you. Now listen here, you homeless, lying tramp, I really regard you as a bad influence. These fancies are contagious. There ought to be a quarantine in mischievous ideas. Eccentricity is immorality. And if a species is rare, it follows –

ANGEL – that it is not fitted to survive.

[CRUMP is taken aback that another one of his sayings has been memorised.]

CRUMP Yes… indeed… my philosophizing does appear to be drawing disciples. But you must go. Hilyer stands on the edge of a precipice. If he stays this course a day longer, the ruin to his reputation will be irreversible. He shall live the poor, miserable, shunned life of another in this village. Now I implore you, for Hilyer’s sake, go.

ANGEL Where shall I go?

CRUMP That’s not my affair. Go where you like. Only go. I bid you good day.

[CRUMP opens the front door.]

ANGEL Not so hastily.

CRUMP I beg your pardon!

ANGEL This all stems from how I was found, does it not?

CRUMP [Hesitantly] From that and other considerations, yes.

ANGEL Perhaps you could explain my state of undress, Dr Crump, in the bracken.

CRUMP [Astounded] What are you suggesting?

ANGEL Hilyer at first though I was two creatures, perhaps the beast with two backs I’ve read of in your Shakespeare, before he fired his gun. I wonder … who could I say was that other in the tryst?

CRUMP That is the most vile … I should have you flogged. Why, I’m speechless.

ANGEL I, however, am not. Don’t consider your position so high that people wouldn’t be quick to think ill of you, Dr. Crump. Apparently the thinking of it is enough.

CRUMP That – that is blackmail! [With a hint of lewdness] Or do you propose something else?

ANGEL [Amused] No, merely money.

CRUMP [Sarcastically] What does an angel want with money?

ANGEL A fallen angel. It seems you need money on this world to get by. And to avoid … [saying the word with horror] work.

CRUMP [As if he’s finally gotten to the source of ANGEL’S motives] Of course! You are revealed to be a slyer, more unscrupulous creature with each meeting … But I’ll deny any imputation you make. The shame will fall on you for slander.

[CRUMP opens the door its full arc for ANGEL to leave.]

ANGEL Again, not so hastily.

[CRUMP turns.]

CRUMP The damned insolence!

ANGEL Who am I, dear doctor, to have shame fall on me? That is no threat. I have no name, as you’ve said yourself, but you do. No address but here, merely a single stop in long journey, but which is your home. No money but … but charity, while you have your … respectable profession.

CRUMP You’ll have a name. You’re from somewhere.

ANGEL Cloud 9?

CRUMP Bah! You’re no angel.

ANGEL No, nor you a saint.

CRUMP And … and what do you mean by that?

ANGEL That it wouldn’t be the first so-called ‘sordid’ situation in which you found yourself implicated. Your fellow humans have overlooked your indiscretion once on account of your prospects and good name, but will they twice? Apparently even the excessive class cannot abide grossness.

CRUMP To … to what incident do you refer?

ANGEL In one word, Baring.

[Pause.]

CRUMP What do you want?

ANGEL For you to invite me into good society. And Hilyer also. Your soiree tomorrow noon should suffice as a first step.

CRUMP Very … Very well then. But if no one else at my soiree can bring himself to accept an angel into good society, then be that on your halo!

[CRUMP leaves. HILYER enters a moment later.]

HILYER Baring agreed to jump the back wall, thank goodness.

ANGEL I like your Dr Crump very much.

HILYER Dr Crump! I forgot! Has he left?

ANGEL A first-rate fellow.

HILYER [Looking at ANGEL questioningly] Yes … yes, a first-rate fellow … But has he left?

ANGEL All too soon.

HILYER Does he …? Like Baring …? I mean, is the same suspicion …?

ANGEL That we are lovers?

HILYER Lovers? Us?

ANGEL Naturally.

HILYER That is hardly the word! My head has cleared in the last hour. You are not responsible for your hallucinations. A fever from the injury to your wing – that is all. And what you speak of as occurring was quite impossible. Angels are from heaven.

ANGEL But may end up in hell. I’ve been reading your bible.

HILYER Hell …? To not believe but still believe in that …? It was a fever, due to your injuries.

ANGEL Under whose hallucinations you also suffered?

HILYER [Mock innocence] What hallucinations?

[ANGEL regards HILYER with a cruel eye. He decides on a different tack.]

ANGEL Doctor Crump has invited me, and reinvited you, to his soiree.

HILYER Perhaps I should go alone.

ANGEL But he invited us. Dr Crump and I laughed over the matter of the last few days.

HILYER Laughed?

ANGEL He said he had come to his senses. There was nothing more natural than a Vicar taking in a guest, a respectable guest at that, one from a good name.

HILYER [Excitedly] You have a good name? A good name, really?

ANGEL [Defiantly] Yes. Angel.

HILYER Angel? Yes… yes I’ve heard of that family.

ANGEL Possibly, if one enquired, it might be found that my parentage was upper middle-class, that I am made of the finer upper middle-class clay. A true, worthy gentleman, in fact.

HILYER Yes … yes … you’re bearing positively confirms the fact.

ANGEL Or perhaps, after all, I am simply an angel.

[HLYER becomes miserable once more.]

HILYER [Apologetically] Only exceptional people appreciate the exceptional.

[ANGEL begins pacing, plotting.]

ANGEL [Slowly] Only exceptional people appreciate the exceptional. Yes, possibly, after all, I shall become a man.

HILYER What? No, not that!

ANGEL So you do believe?

[HILYER turns away.]

HILYER I can’t afford to.

ANGEL In that case, I shall most definitely become a man. I may have been too hasty in saying I was not. You now say there are no angels in this world. Who am I to set myself up against your experience?

HILYER [Remorsefully] But you are without doubt too exquisite to be of this earth! Don’t say that.

ANGEL If men say there are no angels – clearly I must be something else. I eat – angels do not eat. Already, I have a penchant for a carnivorous diet. I may be a man already?

HILYER Yes … yes, already … These scandals take years to die. The pleasure of … of days … Are you staying days or weeks? No, it must be days (how could it be otherwise – I’ve promised Sir John Gotch) mustn’t be the ruin of one’s reputation. Otherwise, the world will continue to come to pieces about me. Have I lived a virtuous, celibate life for thirty odd years in vain? The things of which these people think me capable!

ANGEL Are they wrong?

HILYER It shows you how an angel’s visit may disorganise a man. Are they wrong? I suppose there is no adamantine ground for any belief. Are they wrong? But one gets into a regular way of taking things. I have not felt so stirred and unsettled since my adolescence. In short, I am afraid. Dr Crump’s re-invite to his soirée proves I have averted disaster but … another slip and … Yes, let’s say you arean ordinary man with a … ah, that’s it, a weakness for wading, and you had gone wading in the Sidder, and your clothes had been stolen, and I had come upon you in that position of inconvenience; the explanation I have to make to Mrs. Mendham would thus be shorn of the …

ANGEL Exceptional?

HILYER [Dismally] Yes. [Pause]. You catch on so quickly to our ways.

ANGEL The art of slumming it.

HILYER Do you think the rest of the village, taking Dr Crump’s lead, will … will find that they, too, can appreciate that more earthly explanation of your appearance?

ANGEL That is what I am counting on. An earth angel, if you like.

HILYER Yes, there isn’t much toleration of the supernatural – even in the pulpit. Nowadays people are so very particular about evidence. Temporarily at least I think it would be best if you behave as a man.

ANGEL That is exactly what I propose to do.

Scene 8

DR CRUMP’S

ANGEL plays a beautiful piece, perhaps something from Ravel, finishes his recital and bows. There is clapping from those gathered: HILYER, CRUMP, RICHARD, JESSICA, HETTY and AGNES. {Note: if no actors are doubling up on roles, then MENDHAM and GOTCH may also be present}. RICHARD, JESSICA and HETTY are talking in their own group.

JESSICA [Profoundly moved] Beautiful … utterly … beautiful.

RICHARD A little amateurish, to my mind. [Pause.] A great gift, undoubtedly, but a certain lack of sustained training. [Pause.] Those notes were a little fast … but he did fit them all in. [Pause.] Well, yes, he’s very pretty. But the ultimate test of a man is his strength. [Pause. Looks at his wife JESSICA looking at ANGEL] I wonder what mate he might attract.

HETTY It’s the effeminate man who mates the masculine woman. When the glory of a man is in his hair, what’s a woman to do?

RICHARD Quite … Quite! Couldn’t have phrased it better myself, Hetty. [To JESSICA] What say you to that, wife?

JESSICA [Endeavouring to pull herself together] His tie is all askew. And his hair – it hardly looks as though he had brushed it all day long.

RICHARD Yes … yes. Less locks than lock Nesses – ha! Hear that one?

HETTY Shush, Father. His playing was exquisite and his beauty divine.

[RICHARD looks at HETTY astounded.]

RICHARD Well, yes, I wouldn’t mind a word with him about technique. I suppose by not having any technique at all, you may just chance upon the odd new one, now and then.

[RICHARD approaches ANGEL, who is standing with HILYER.]

HETTY Mother, I’m glad Father played before Mr Angel, and not afterwards.

JESSICA Yes … yes, your father the anti-climax.

HETTY Life’s not much fun, is it, Mother?

JESSICA No, not much fun. [Making herself bubbly] Yes, beautiful, utterly beautiful music! Music stirs something in me, Hetty. I can scarcely describe it. Who is it says that delicious antithesis: Life without music is brutality; music without life is … Dear me! Perhaps youremember, Hetty? Music without life … It’s Ruskin, I believe. Surely with such a delicate touch, Dr Crump’s guest must be well known. Something of a celebrity. In fact, come to think of it …

[Meanwhile, RICHARD, who tried to introduce himself to ANGEL without much success and to HILYER’S embarrassment, instead accosts CRUMP. CRUMP is still moved by the music he has heard.]

RICHARD Rummy looking greaser. Wants grooming. No manners. Grinned when I tried to shake his hand just then. Thought I did it with some chic. Dr Crump, I know you invited him to perform at your soiree here, but what’s your honest assessment of this chap?

CRUMP [Still befuddled] My honest assessment …?

RICHARD I asked him about his technique. Said he didn’t have one.

CRUMP His music … it invoked … longing for … for fantasia.

RICHARD Fantasia, yes. Can’t say I disagree with you on that. I don’t admire these complicated pieces of music. I have simple tastes, I’m afraid. There seems to me no tune in it. There’s nothing so much I like as simple music. Simplicity is the need of the age, in my opinion. We are ever so subtle, Dr Crump. Everything is far-fetched. Home grown thoughts and ‘Home Sweet Home’ for me. What do you think?

CRUMP Admirably … sensible of you, Mr Jehoram, admirably sensible.

RICHARD Yes … My wife and daughter are completely taken in, of course. Naturally that sort of composition appeals to the irrational in creatures. [Becoming less sure of his own rhetoric] It did sort of speak of a faraway place, his music, somehow … didn’t it?

CRUMP Insensibly … sad.

RICHARD Capricious and grotesque.

CRUMP I have never felt anything of this kind with music before.

RICHARDS No. [Pause; honestly] I shall never play again.

[The two look at each other, embarrassed. CRUMP pulls himself together.]

CRUMP Oh what’s this, Mr Jehoram? Two sensible chaps making themselves maudlin over a trifling air. By tonight, we will have forgotten it. Mozart is more calming. Yes, I really feel Mozart is more moral. I only ever feel happy when I listen to him.

[HETTY approaches.]

Why, young Miss Jehoram! Young? I can’t say that much longer. How you’re growing up.

HETTY That Mr Angel is an unusual talent, Dr Crump. Wherever did the Vicar find him?

CRUMP [Embarrassed] I’m sure I have no idea, Miss Jehoram.

RICHARD Hetty did not mean the bracken beyond the copper gate, Dr Crump.

CRUMP [Turning red] No, quite.

HETTY I never suspected the Vicar was nearly such an interesting man.

CRUMP [Grumpily] Hm, yes, you are growing up.

HETTY ‘Mr Angel’ is a nom de plume, I believe? He must be incognito. Mother says she saw him at Vienna, but she can’t remember the name.

CRUMP What was that? [Sceptically] She saw him at Vienna, did she?

RICHARD Did she say that, Hetty?

CRUMP I’m sure Mr Angel gets around, Miss Jehoram, but not quite so far as Vienna.

HETTY It must be the same youth by the way mother describes him; such cleverness with his instrument.

CRUMP Indeed!

HETTY You will not even allow, Dr Crump, the piece’s marked originality?

CRUMP Too grown up.

RICHARD Hetty, dear. Don’t persist in –

CRUMP You want my opinion of his playing, Miss Jehoram? A little involved, to my mind. I have heard it before somewhere – I forget where.

HETTY Perhaps, Dr Crump …?

CRUMP Yes?

HETTY In Vienna?

RICHARD Hetty!

CRUMP [Controlling his anger] Miss Jehoram, I am sure I did not.

RICHARD Nonetheless, Dr Crump, a mysterious fellow, all the same. The Vicar obviously knows all about him but he is so close.

CRUMP Too close, yes. If you’ll excuse me.

[CRUMP joins HILYER. RICHARD watches as JESSICA approaches ANGEL.]

RICHARD Do you know, Hetty, I’m half inclined to believe your mother’s story.

HETTY How good of you, Father.

RICHARD Perhaps Mr Angel is in disguise.

HETTY If you call nothing a disguise.

RICHARD Hetty!

JESSICA Yes, Father?

RICHARD As Dr Crump says, it is a grave sign for good society when no one blushes anymore.

JESSICA And I blush so prettily, don’t I, father?

RICHARD That you do. When you do.

[AGNES approaches.]

AGNES Mr Jehoram, I hope you are not taken in by this impostor?

RICHARD [Disconcerted] Taken in, Mrs Mendham?

AGNES If we guardians are not careful, the simple folk may even warm to him.

RICHARD You allude to Mr Angel?

AGNES Who else? The simple and the … [nodding in HETTY’S direction] … young may even become infected by his obviously lax morality.

RICHARD Lax morality, Mrs Mendham? Surely?

AGNES I for one remain unconvinced by his story.

RICHARD May one inquire in what way you remain unconvinced, Mrs Mendham?

AGNES Well … well, as for that very convenient explanation for why he should be naked in the bracken … it doesn’t wash.

HETTY Washing was apparently what he was doing.

AGNES [To HETTY; acidly] Humph! [To RICHARD] The young, Mr Jehoram, the young have already become infected by his indecencies. Do you now appreciate the gravity of this matter?

RICHARD [Looking at HETTY worriedly] Yes … yes, Mrs Mendham.

AGNES And the confusion over his name – the Vicar laughing off that he should ever say Mr Angel was actually an angel – well, my husband for one, swears the Vicar swore otherwise. Unconvinced, Mr Jehoram? I remain completely unconvinced.

RICHARD Your admirable sobriety on this issue, Mrs Mendham, has sobered me in turn.

AGNES I should think so.

RICHARD Thank you.

[AGNES leaves.]

HETTY What a nasty, horrid –

RICHARD No, no, no, Hetty, enough!

HETTY That young man is brilliant, mysterious! He is –

RICHARD No, no, no, Hetty, that Mr Angel is definitely not a genius, disguised or otherwise. He is … he is … [Becoming distracted by what he observes of ANGEL and JESSICA’S close proximity to each other] Why, my wife is practically sitting on that charlatan’s lap, he has sidled up so close! The young and old alike are in danger!

HETTY Mother is quite taken with him, Father.

[RICHARD raises an eyebrow.]

RICHARD [Explosively] What?

JESSICA [Quickly] Taken with his playing, I mean.

[Meanwhile, JESSICA sidles even closer to ANGEL.]

JESSICA Well, Mr. Angel, I for one am intrigued.

ANGEL Intrigued? With what or by whom?

JESSICA You must admit there is something frightfully romantic about the thought of an angel, even a pretend one, right here, in our tiny little village.

ANGEL Romantic?

JESSICA I wish I did not read. Only we poor women – I suppose it’s originality we lack. And down here we are driven to the most desperate proceedings.

ANGEL Desperate proceedings?

JESSICA Books. You even look like something out of a book.

ANGEL How do you mean?

JESSICA Dreamy. [Quickly, aware she has possibly gone too far with the preceding comment] What was the name of that charming piece, Mr Angel?

ANGEL It has no name.

JESSICA [After a pause] I think music ought never to have any names. Who then, may I ask, was it by?

ANGEL By? Why, I played it out of my head.

JESSICA [After a pause] Out of your head? Did you really make that up yourself? As you went along? I think improvisation comes within the limits of permissible originality. Mr Angel …?

ANGEL Yes?

JESSICA I have so longed to have a quiet word with you, to tell you how delightful and innocent I found your playing.

ANGEL I’m glad it pleased you.

JESSICA Pleased is scarcely the word. I was moved – profoundly. The others did not understand … I was glad you did not play with him.

ANGEL Your husband?

JESSICA When he insisted on a duet, you insisted on playing solo. There is nothing less romantic in a woman’s life than her husband. But Iworship music. I know nothing about it technically, but there is something in it – a longing, a wish … You understand. I see you understand. Such deliciously liquid eyes.

ANGEL Tell me, Mrs Jehoram?

JESSICA Jessica.

ANGEL Are you separated from your world?

[JESSICA is taken aback by this seemingly out-of-place comment, but is not unmoved.]

JESSICA [Feverishly] As you from yours? There are those who cannot live without sympathy. Do you look for sympathy, Mr. Angel?

ANGEL I think … I think I have found it. [They lean closer] Her name is …

JESSICA Yes?

ANGEL Delia.

JESSICA [Standing up] Delia! Why, no, not that little housemaid at the Vicarage? I never did! To make me your confidant in an intrigue with a servant. Really, Mr. Angel, it’s possible to be too original.

[HILYER, CRUMP, RICHARD, HETTY and AGNES rush over.]

CRUMP What is the matter, Mrs Jehoram?

RICHARD Jessica, are you quite all right? Such an outburst!

HILYER Angel, you haven’t been guilty of an infelicity?

ANGEL An infelicity?

CRUMP Hilyer, I must really ask you to manage your charge.

HILYER My charge? Dr Crump, I’m really not his guardian –

ANGEL You disown me?

HILYER I …

[The others look to HILYER to see whether he will defend or censure ANGEL. HILYER cannot mouth any words. Disappointed and hurt, ANGEL leaves.]

JESSICA I … I am disgraced forever.

RICHARD Drunk! He was obviously drunk – like his music.

JESSICA I was trying to keep him quiet, by humouring him. He told me he is in love with the Vicar’s housemaid!

HILYER In love?

JESSICA I almost laughed in his face.

[JESSICA starts laughing now, quite madly. Her laughter turns to sobs.]

RICHARD No one likes to be duped. I’m taking her home.

[RICHARD, JESSICA, HETTY and AGNES leave. CRUMP turns to HILYER.]

CRUMP So, he is carrying on with your servant-girl? I must say, Delia has always seemed to me to display a cheerful readiness to dispose of her self-respect for half-a-crown.

HILYER In love?

CRUMP It may be a union frowned upon, but at least it is a love they won’t have to hide. Hilyer, I told you, you haven’t the robust constitution for this. Since the slight turmoil of your youth, for twenty years now you have held this village living and lived your daily life, protected by your familiar creed, and by the clamor of the details of life. But now, that hard-won submission, fought for in both of us, from the revelation of the music we’ve heard here today, may be irrevocably shattered. What I fear most for our futures is that, interweaving with the familiar bother of our fellow, persecuting neighbours, will be an altogether harrowing sense of strange new things, glimpsed as if through a flapping tent door but never entered, the fabulous, rarely to be enjoyed, carnivals of a better life.

Scene 9

FOREST

BARING is secretly following HETTY. HETTY moves with purpose.

BARING Miss Jehoram?

[HETTY stops and turns around. BARING reveals himself.]

HETTY You? I’m supposed not to talk to you.

BARING And have you been told why?

HETTY Why, is there something to tell?

BARING Dr Crump’s soiree seems to have finished early.

HETTY Yes, Mr Angel was quite a sensation.

BARING You mean to say he caused offence?

HETTY To … some.

BARING But not to you? Is that why you follow him?

HETTY [Bristling] Have you been following me, Mr Baring?

BARING Only because we pursue the same object.

HETTY And why should you pursue Mr Angel?

BARING As a means of escape.

HETTY As a means of … Explain yourself?

BARING He has undoubted gifts, yes?

HETTY Undoubted …

BARING A real talent…?

HETTY A real talent.

BARING But, as the briefness of this afternoon’s soiree demonstrates, unformed manners which –

HETTY – if properly moulded, could see you both to success?

BARING You read me too well. But, if I am not mistaken, a similar motive may be divined in you. They are not an imaginative race about here; most do not long for the circumscribed landscape, yet broader horizons, of cities. You, I believe, feel you will surely shrivel if you stay here. You cannot learn to live chiefly upon Burgundy and the little scandals of the village; commit wholly as a sturdy Broad Protestant and sit, concerned, on the Village Council; take no interest in politics, yet nonetheless remain an active enemy of ‘that Gladstone’; drive through Siddermorton with your sparkling pair of greys where you call on Bessy Flump, the post-mistress, to hear all that has happened, which no matter how you turn it over isn’t very much, then upon Miss Finch, the dressmaker, to check back on Bessy Flump; and all the while believe any of what you say or even your life amounts to a pittance.

HETTY Let me complete the picture for you, Mr Baring, since you seem to have made a fairly exhaustive study of me. My mother is older than most mothers of girl’s my age. As a poor cousin, and despite a brief sojourn in Europe in search of an aristocratic husband, she only avoided perpetual spinsterhood when my father happened to pass through our ‘unimaginative’ village and take a liking to her. By marrying him, she thought to save herself at least one fate, spending the rest of her life here. To her horror, he decided he liked Siddermorton’s ‘cosy quaintness’. My mother was thus doubly disappointed. Make no mistake: with Mr Angel, I will insist on a London wedding. Despite your obvious skills of observation, honed as a result of your outsider’s status, no doubt, I don’t believe you are any competition for me, Mr Baring, and expect you to cease shadowing me at once.

[HETTY turns to continue her pursuit.]

BARING Not so hastily.

[HETTY stops and turns around, incensed.]

HETTY I beg your pardon?

BARING Miss Jehoram, although we both pursue the same object, we also share the same obstacle in our path.

HETTY That servant girl!

BARING Yes, Delia. I propose we unite until we have her safely dispatched. After that, may the best man win.

HETTY Best man? Ha!

BARING You nonetheless take my meaning.

HETTY Well, then, what do you propose?

BARING To get her away from him.

HETTY Obviously. How?

BARING First, tell me all you know about Delia?

HETTY I haven’t met her. Apparently Father found her for the vicar. He first found her for us but Mother said we had no need of another maid, even though at the time Mother was complaining that the one we had wasn’t enough.

BARING Your mother saw Delia, obviously?

HETTY Yes? Why is that obvious?

BARING And you – you’ve never seen this Delia?

HETTY No …

BARING Nor heard her described?

HETTY Only as having ample attributes.

BARING Naturally. Ample attributes. Go on.

HETTY The story is that Delia was down on her luck. I think it rather charitable of Father. I hadn’t thought of him quite so. We should really help the less fortunate. Don’t you agree? Especially when –

BARING Miss Jehoram, let me show you Delia.

HETTY Show me? How?

BARING She and Mr Angel are under that poplar tree on yonder hill, enjoying a clandestine tryst. My opera glasses.

[HETTY stares, morbidly impressed, at the opera glasses BARING has revealed from beneath his coat.]

HETTY You really are something of a dedicated observer.

BARING It is the position I have been consigned to in this village. Take a look.

[HETTY looks through the opera glasses.]

HETTY Is … is that her?

BARING Yes.

HETTY She’s … she’s …

BARING Utterly exquisite, yes.

HETTY [Jealously] She’s … Should a servant wear her hair so?

[HETTY holds her hair up in imitation of what she has evidently seen through the opera glasses. BARING notices with some malice. HETTY quickly drops her hair and acts unconcerned.]

BARING Miss Jehoram, will you help me to help Delia once more?

HETTY Help her? But –

BARING Yes, Miss Jehoram, help her.

HETTY I don’t understand where you are going with this.

BARING You read for Miss Papaver, do you not? She of the ruddled countenance and ropy neck?

HETTY And spasmodic gusts of vile temper!

BARING One of your charitable duties?

HETTY And how I hate that smelly old rag! Father insists on charitable duties, especially for others to do. That is why I was so surprised at his wanting to take Delia in.

BARING And yet, despite your charitable duty in respect to Miss Papaver, surely she must need more than someone to read to her in her dotage? Perhaps you could suggest to your father a servant-girl?

HETTY Delia, I suppose? And have to stand in direct comparison with her?

BARING And then when your father broaches the topic with Hilyer of Delia’s new placement, something tells me Hilyer will agree to it only too readily.

HETTY Yes, well, we should help the less privileged classes as much as we can. But after a time, they must help themselves.

BARING I’m sure she’s helping herself.

HETTY You’re wicked.

BARING How wicked are you? Will you help you by helping her?

HETTY How would engineering to bring her into Miss Papaver’s home help me?

BARING Come now, Hetty, you’re smarter than that. Because it will take her away from Mr Angel.

[Pause.]

HETTY I’ll try my best.

BARING Best you had.

HETTY But Hilyer has given Mr Angel a deadline to leave Siddermorton anyway.

BARING Then you understand how little time we have left to get to him without such a pretty distraction.

HETTY I’ll do my utmost.

BARING That is better. I see it in you, Hetty, something invidious as it is in me. People disgust us as much as we disgust ourselves and we have little sympathy for either, but we will not go without.

HETTY Don’t compare us! And remember, Mr Baring, once Delia is dispatched …

BARING May the best man win.

HETTY That best man may be Mr Angel. I shall begin to work Father straightaway.

[HETTY departs the way she came. ANGEL appears from the other side. He stops on seeing BARING.]

ANGEL The fox?

BARING Only today, Mr Angel, you look like the one caught out.

ANGEL Caught out?

BARING You are learning shame, possibly?

ANGEL I have nothing to hide.

[ANGEL makes as if to keep moving.]

BARING Wait, will you spare me a moment?

ANGEL What for?

BARING I have a proposition for you, just as you no doubt have just made a proposition to Delia.

ANGEL A proposition? Hardly. I don’t even understand the necessity of your sentence of marriage. In fact, I have broken off things with Delia.

BARING [With sudden hope] You have? Why?

ANGEL I am tasting this world without thought for repercussion. Besides, there is another who owns my heart.

BARING [In raptures] Oh, my angel.

Scene 10

LIVING ROOM

HILYER is pacing about. Now and then he checks his watch. ANGEL enters.

ANGEL You are still up?

HILYER Considering how short is the time we have together, you might perhaps have come back earlier – from wherever it is you have been.

ANGEL It is you who are sending me away.

HILYER Yes, my promise to Sir John Gotch. And now Dr Crump.

ANGEL You have made a pact with him also?

HILYER Oh, it’s not you that’s the trouble. I perceive you have brought something strange and beautiful into my life. It’s not you. It’s myself. If I had more faith either way. If I could believe entirely in this world, and call you an Abnormal Phenomenon, as Crump does. But no, Terrestrial Angelic, Angelic Terrestrial … See-Saw. [Pause.] And now the social collapse of this afternoon – it’s hopeless … You are so very fundamental, you know.

ANGEL Do you mean material?

HILYER Yes, material. And that is hard to deny. Oh, life’s not much to be had. To die – to die young for a cause – that would be grand.

ANGEL Why die for a cause? I’d kill for one.

HILYER I must interpret that in the way most pleasing to interpretation.

ANGEL You mustn’t ‘must’.

HILYER End it now – while you’re still young.

ANGEL You can, if you so desire. Since this life is finite, I wish to see it out to the end – in comfort. You are becoming tedious. Baring has saved enough for us to go to London.

HILYER Baring?

ANGEL Since he is so good at dishing out advice, I wanted to see if he could take it. Instead of trying to resurrect the respect of his good name, he has agreed to invent another.

HILYER Baring?

ANGEL No, another. In London.

HILYER [Exploding] You found him hideous!

ANGEL Did I?

HILYER You know you did.